How would the Gospel shape our engagement with music? Christ is Lord over all our work and our pleasure so his sweeping salvation plan must apply even to the pieces we’re practising, mixing or dancing to, but somehow but it can be difficult to see.

Ted Turnau sets out a useful framework for what he calls ‘A Christian reading’ of popular culture in his book Popologetics.[1] His wide ranging examples include films, popular songs, and Twitter, but omit music without texts or visuals and classical music in general.[2] After hearing him speak about his work at Word Alive 2018, I was bursting to think through how this could apply to a broader range of music. I also want to explore how to apply his framework to musicking, by which I mean acts of music making or musical happenings, to how we do music rather than just to pieces of music as if they were static objects – more on that later.

What is being communicated?

We are looking at worldview rather than censorious criteria. So, rather than simply asking ‘does this piece contain nudity and swearing?’, we are asking about the relationship between the truths of the Christian Gospel and the subtext, underlying beliefs, or values that are communicated by the music/musicking. All music is a product of and propagator of ideologies, beliefs, and ways of looking at the world – take a piece you are working on and ask ‘is there hope?’, ‘is there a telos, an end goal?’, or take an act of musicking and ask ‘what are the priorities here?’, ‘what hierarchies does this act create?’ Our own worldviews will affect how we answer those questions, as will the worldviews of the other musicians, authors of music histories, listeners, producers etc who are also connected to the music. The question is: ‘how do these worldviews interact with the Gospel?’

I am using the word ‘Gospel’ as shorthand for the ways that God has and is working through his creation to bring about the perfect new creation. This includes truths about the sovereignty of God, the goodness of the world that God has made, the reality and horror of sin, humanity’s yearning for and dependency on God (even if they don’t realise it), Jesus’s perfect life and sacrificial death, redemption, atonement, grace, love, community, hope of heaven, certainty of new creation, judgement, forgiveness… The glorious list could go on and on! Believing in these things will affect the way that we view the world, and how we identify, listen to and respond to other people’s worldviews.

Musicking

Ted Turnau’s book focuses on reading cultural artefacts as texts, as static objects rather than things which happen.[3] I would like to expand his framework as we think about music more widely, equipping us to apply Turnau’s ideas to the ways that we do music in practice. There is a variety of jargon for this – some may understand what I mean if I say music is something that happens rather than something that is. Other may be acquainted with the term ‘musicking’, a useful word coined by Christopher Small that helps us to think of music as a verb rather than a noun.[4] The point is that music is not an object; it is always something that we are doing even if that is reading a score or listening to what seems to be a perfect rendition.

What this means is that the meaning, mood and subliminal messages of a piece of music do not necessarily stay the same; they change as the way we engage with the piece changes and as we interpret them differently in different places. A meaningful reading of a piece will take this into account. Of course we say things like ‘Mozart’s piano sonata bubbles with fun’, but that is probably only true when it is in the background of a tea party. When we play it in a competition, it brims with anxieties; when we teach it to a child who won’t practise, it reeks of pathetic frustrations; when we hear it and we are heartbroken, it is like rubbing salt in the wound. We can engage with the same piece in lots of different ways and this variety ought to affect our reading of it. For example, if a local youth orchestra tries its parents’ patience with a Bruckner symphony, it is a very different musical event to when the same symphony was played at a Nazi rally in the run-up to World War II, or when a conductor practises it in front of their bathroom mirror, or when a stressed banker hears it on the radio and sighs as he drives home after a long day. It might be the same piece, but in each scenario the music serves different functions, the musicking has different goals, and the Gospel is reflected and distorted in different ways. Our reading of Bruckner’s symphony will be less abstract and more meaningful when we consider the 'when', 'how' and 'who' of its happening rather than just the 'what' of the score and programme notes. The 'what' is still important - in fact it has its own column in the table I have outlined below - but it morphs and interacts with living events, and it is these specific events, the musicking of the piece, that reside in the right-hand column.

Five key questions

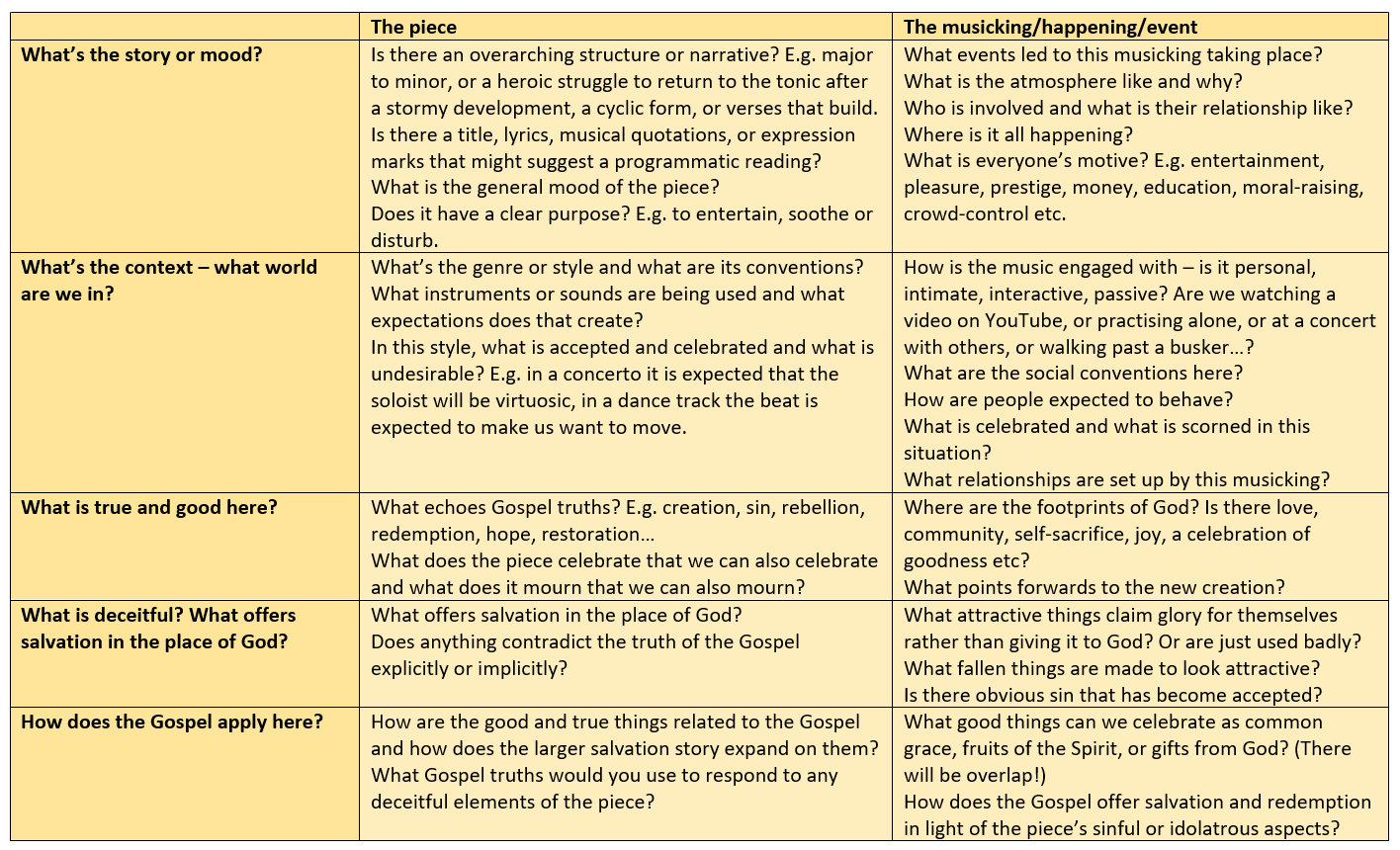

Ted Turnau lays out five questions to think about when considering a popular-culture text.[5]

- ‘What’s the Story?’ Unpack the narrative: its plot, characters, conflict, key moments, structure, setting, recurring motifs, narrator’s tone, mood.

- ‘Where Am I? (The World of the Text)’. What is the medium, what imagined landscape does it create and how do we inhabit it? Is it a novel, computer game, or film, and how do most people engage with that medium? It could be a world that embraces us, or that gets under our skin, or that we interact with, or that gets fixed in our minds. What counts as good or evil is this world? What do people strive for?

- ‘What is Good and True and Beautiful in This World?’ There will be moments of grace that Turnau calls ‘footprints of God’ because ‘they point to his blessing and purpose in the world’.[6]

- ‘What Is False and Ugly and Perverse in This World (and How Can I Subvert It?)’ Where are truths subverted and idols established? What is worshipped or called on for salvation in the place of God?

- ‘How Does the Gospel Apply Here?’ Show ‘the relevance of the gospel and the perspective that it alone reveals’.[7]

Here is how I would adapt these questions for considering a wider range of music and musicking:

Some examples

See this extra resource here for examples of how four young professional musicians have filled in this table, exploring how the Gospel is reflected and distorted as they (1) practise solo instrumental pieces pieces by Hindemith and Brahms, (2) take part in a professional performance of an oratorio by Handel, and (3) compose a contemporary choral piece with texts taken from the diary of someone suffering with depression.

Your turn

Click here for a blank copy of the table which you can then download (File -> Download), and fill it in for a piece you are working on or have listened to or watched recently….

And after you've done so...

So now what? I would recommend scanning through the table and praying through what you are thankful to God for, anything you need to ask for forgiveness for, and about any idols you need God’s help to avoid as you engage with this piece. Then go ahead and make decisions about how you practise, or listen, or programme the piece in light of what you have been thinking and praying about. It might not look very different to before, or it might lead to fresh new approaches, or a decision to leave a particular piece out of your repertoire for a while. You might find using this table for a few pieces over the next few months helpful in building habits of thoughts that encourage you to think intelligently about the musicking you are doing in light of the Gospel.

I would love to know if you’ve found this helpful in your musicking so please let me know by emailing music@uccf.org.uk. If you have filled in a table and are happy to share it I would be really interested to see how this framework does or doesn’t work for you, and other students might also find it really encouraging to see how you are also working through these things so send it in!

Troubleshooting

- Q1: Isn’t this all just subjective? Am I just making stuff up?

- A1: It is subjective insofar as what you write will depend on your point of view where you are at one point in time. That does not necessarily mean it is all fairy tales or useless. Considering your musicking in light of the Gospel will hopefully help you to see Christ at work in all of creation and help you to honour him with your whole life, even if your considerations are subjective and only applicable to you at this time rather than objective and applicable to everyone everywhere for evermore. The more informed you are, the more helpful your subjective view is likely to be to others.

- Q2: What’s the point?

- A2: There are several points:

- To see how the Gospel applies to all of creation and that Christ is Lord of all

- To be driven to worship and thank God

- To be on our guard against idols and unhelpful beliefs or assumptions that often lurk just out of our awareness whilst we are musicking

- To change the way we habitually think about, talk about, and do music in light of the Gospel.

- Q3: What if I don’t have much to say in some of the boxes?

- A3: That’s fine! Leave some boxes blank by all means; don’t feel you have to waffle when there is actually nothing to say.

- Q4: How on earth can I fit my detailed analysis complete with diagrams into one of those tiny boxes?

- A4: It doesn’t need to be an analysis essay. If you are an essayist maybe just write your conclusions.

__________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Ted Turnau, Popologetics: Popular Culture in Christian Perspective (P&R Publishing Company, 2012).

[2] Ted Turnau generally excludes classical music from his area of study because he wants to focus on music that is accessible, widespread and widely received. His discussion of this and his opposition to traditional binaries about high and low art forms in pages 3-7 is absolutely excellent. However, I still believe it is worthwhile applying his ideas to a broader range of music, particularly as so many of us spend most of our time engaging with all this ‘not-popular’ stuff! I must admit I also wilted to hear that classical music is still seen as inaccessible, as I’m sure you did if you have worked in open-access music schemes, community-based arts projects...

[3] Ted Turnau briefly discusses this in his conclusion where he acknowledges that he has not considered the social contexts of popular-cultre texts and refer’s to Jeremy Begbie’s point that ‘music is not a collection of individual works as much as the activity of making and listening to music’. Turnau, p. 320 italics original. Jeremy S. Begbie, Resounding Truth: Christian Wisdom in the World of Music (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008).

[4] Christopher Small, Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening (Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1998). Small writes that musicking creates relationships and meaning lies in these relationships.

[5] Turnau, Chapter 10, ‘Reading and Responding to Popular Culture’, p. 213-246.

[6] Turnau, p. 232.

[7] Ibid. p. 241.